Why the hell should I build this?

Business understanding & data modeling — Part 1/6 of RAG That Works

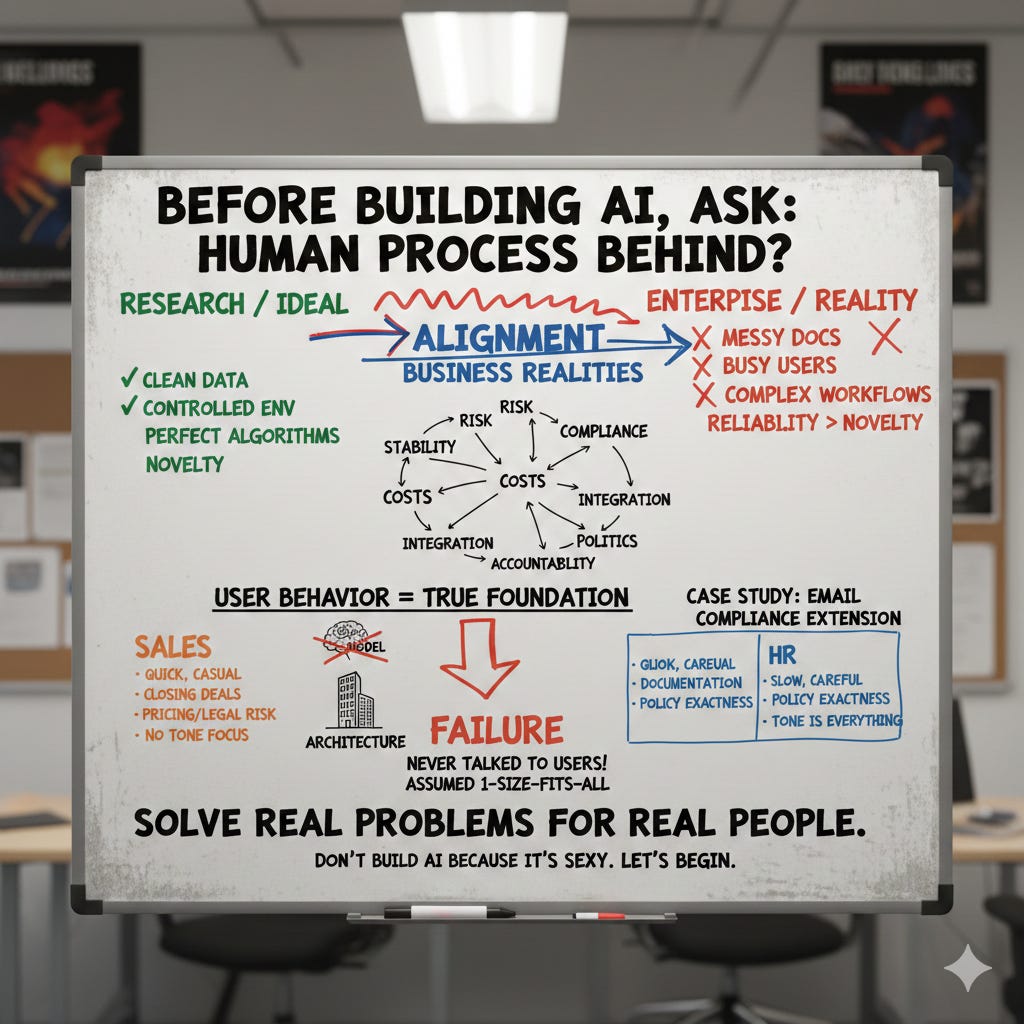

Before building any AI solution, take one minute to ask yourself: what is the underlying human process?

And if i made you curious let me also ask you some questions.

How many times did you feel that your technical decisions are not good?

How many times did you feel the impostor syndrome, because that you are not sure about your decisions?

We’re living in an era where everything moves at lightning speed. Everything must be done yesterday. We’ve stopped focusing on process, on understanding things in depth. We ship fast, we iterate fast, we burn out fast.

I’ve been there. Many times.

And I think this is part of my mission now: to tell you that it’s okay not to be up to date with every new framework and model release. It’s okay to feel the impostor syndrome. What’s not okay is letting that pressure push you into building things you don’t understand or because of hype.

This series is about slowing down just enough to build something that actually works.

PS: AI is not everything. We still bring our own brain, personality, and identity, and that remains irreplaceable.

This series is about enterprise RAG, but more importantly, it’s about building AI systems that matter. Systems that work in the real world, under real constraints, with real users.

Thirteen years in AI taught me many things.

Building six startups and contributing to more than twenty AI-driven projects taught me even more. But the lesson that truly reshaped the way I build systems was this:

Leave your technical ego at home.

I learned it the hard way. Early in my career, I believed technical elegance mattered most, the perfect architecture, the best model, the cleanest algorithm. But enterprise AI doesn’t reward perfectionism.

It rewards alignment, alignment with users, with constraints, with messy business realities.

In the enterprise world, the business side often feels conflictual with our technical instincts. Decision-makers push for certain technologies, certain vendors, certain enterprise solutions, sometimes with little justification, sometimes with none at all.

It’s easy to push back, to feel frustrated, to believe they don’t “get it.”

But if you sit in their position for a moment, you start to understand why those decisions are made.

Risk. Stability. Costs. Compliance. Integration. Politics. Accountability.

These forces shape technology choices far more than algorithms ever will.

Over time, I realized that understanding the business problem is what determines whether an AI solution actually works.

It shapes the architecture, the data model, the evaluation strategy. It determines whether the project succeeds or becomes yet another “AI experiment” that never reaches production.

One of the biggest problems in the AI field today is the disconnect between research environments and enterprise environments. In research, conditions are clean, controlled, ideal. In the real world, especially in manufacturing, logistics, and other heavy industries, documents are messy, users are busy, workflows are complex, and reliability matters more than novelty.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what technology you use.

It matters whether the technology solves a real problem.

But that leads to the key question: what problem are you actually solving?

You cannot answer this by looking at the model.You cannot answer this by looking at the vector database. You cannot answer this by looking at embeddings or chunking strategies.

You answer it by understanding the people who will use your system. The workflow, the expectations, the pain points, the decision making under pressure, tolerance for error, all are component of user behvaiour.

User behavior is the true foundation of enterprise AI.

Not the model. Not the architecture.

So don’t build AI because it’s sexy.

Let’s begin.

Oooops. Did I ask that question?

I still remember the first time this really clicked for me. We were building a Chrome extension for a tech startup, think Grammarly, but all about internal compliance.

The idea was simple: as people wrote emails, the extension would highlight in real time whether their message matched up with company rules, brand voice, compliance policies, sales guidelines, all those internal playbooks every company has but nobody actually remembers when they’re firing off an email before lunch.

Under the hood, we’d put together a RAG system that grabbed pieces of the draft, pulled the right company guidelines, and called out anything that didn’t fit.

The tech was slick, real-time, fast, tidy code. We felt pretty good about it. Then we launched. Two weeks in, usage dropped off a cliff. Sales hated it. HR ignored it. We just stared at the dashboards, baffled. It wasn’t the retrieval quality. Latency and relevance were fine. The problem was we’d built one RAG system and just assumed it would work for two totally different worlds inside the same company. Sales reps write quick, casual, and persuasive. They’re closing deals, not aiming for perfect grammar.

They came to us worried about pricing claims, mentioning competitors, and steering clear of legal headaches, the stuff that can blow up in your face if you’re not careful. Tone or brand voice? Honestly, they didn’t care.

They just wanted to make sure they didn’t say something in a contract they’d regret later. HR, though, was a whole different animal. They wrote at a crawl, choosing every word like it was gold. Their emails doubled as official records, and when things went wrong, people dissected every line. HR needed ironclad policy wording, total consistency, and language that could survive a courtroom years down the road. For them, tone was everything.

Funny how it’s the same company, everyone aiming for “compliance,” but these teams couldn’t have been more different. In the end, each group really needed its own data model.

Here’s where we really blew it: we never talked to users.

We never asked how sales or HR actually worked under pressure. We didn’t watch them write. We built our data models around the documents we had, not the decisions those documents were supposed to help with. That project stuck with me.

Why RAG is different: the end of deterministic thinking

Before we get into the framework, I need to explain why this matters so much more for RAG than it did for previous generations of AI systems.

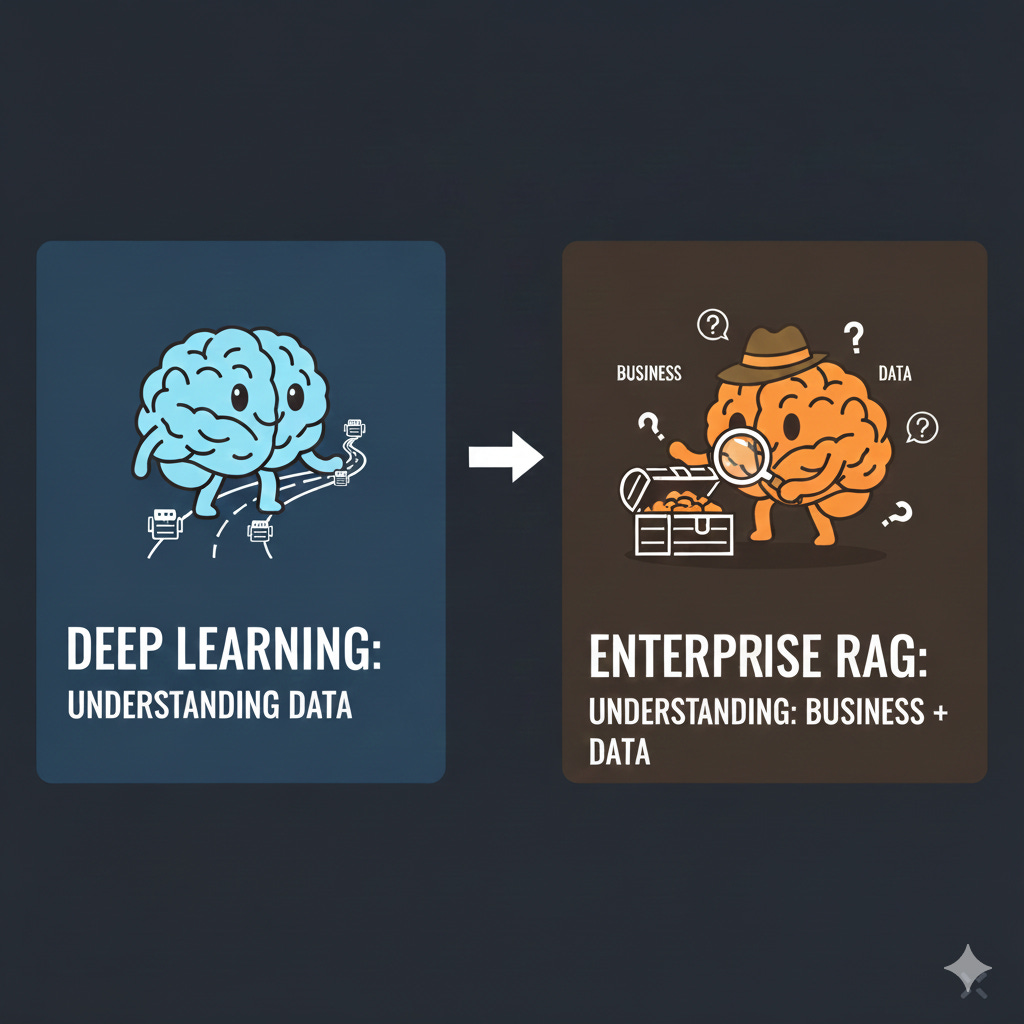

Back in 2017, when most AI work revolved around classical deep learning problems, things were simpler. The entire challenge could be reduced to a fairly predictable loop: collect data, label it properly, train a model, deploy it, and let it make deterministic predictions. The business side was involved, of course, but their role was clearer and narrower, they provided examples of what “good” looked like, and we optimized toward that.

If you were doing image classification, you had images and labels. If you were doing object detection, you had bounding boxes. Everything followed a recipe: you defined the ground truth, you trained the model to match it, and success was measured in accuracy or loss. The rules were rigid, the pipeline predictable, and while creativity was still required, the problem space was bounded.

From a business perspective, it was manageable. You could sit with the client, ask what they wanted to detect or classify, convert that into labels, and build a supervised system around it. The learning objective was explicit. The output was “deterministic”, at least from a thinking perspective.

RAG changed everything.

We transitioned from supervised, deterministic, input-to-label pipelines to probabilistic, context-driven, retrieval-based systems. Suddenly, the same question can produce different answers depending on what gets retrieved, how it gets ranked, what context the model receives, and how the user phrased their query. There is no single “correct” output anymore. There’s a distribution of possible outputs, and which one the user gets depends on dozens of variables that interact in ways you can’t fully predict.

This shift broke the old approach to AI product development.

We no longer ask: “How do we label the data so the model learns what the client wants?”

Instead, the core question became: “What is the client actually trying to achieve, and what information do they rely on to do it?”

In other words: Deep learning required understanding the data. Enterprise RAG requires understanding the business and the data.

When your system is probabilistic and context-dependent, weak business understanding is fatal. You can’t just measure accuracy because there is no single correct answer. You have to understand what “useful” means for this user, in this context, at this moment in their workflow. That understanding can’t come from metrics alone, it has to come from deep knowledge of how people actually work.

This is why the Process Archaeologist framework exists, and why it matters more for RAG than for any previous AI paradigm.

The process archaeologist framework 🕵️♂️

Over the years, I kept running into this same failure, different industries, different clients, same story. So I developed a methodology I now apply before writing any code: the Process Archaeologist framework.

It starts with one question: “Which human process am I trying to support or replace here?”

One minute of thinking. That’s all it takes. But I’ve seen teams spend six months building retrieval systems without ever asking it properly.

I chose the word “archaeologist” deliberately. You’re not inventing new processes, you’re excavating existing ones. Somewhere in the organization, people are already doing this work: manually, in spreadsheets, through legacy systems held together by undocumented workarounds. Your job is to understand what’s actually happening, with all its quirks, exceptions, and accumulated human judgment.

Most technical teams get this wrong. We’re trained to optimize, so when we see a messy process, we want to redesign it immediately. But those “inefficiencies” often encode business logic nobody mentioned, edge cases that matter twice a year, or politics that determine adoption.

The framework consists of four phases that typically span one to three weeks, depending on the complexity of the domain and how alien it is to your existing experience.

The goal is not to become an expert in your client's field, but to understand their work deeply enough that your technical decisions become informed by reality rather than assumption.

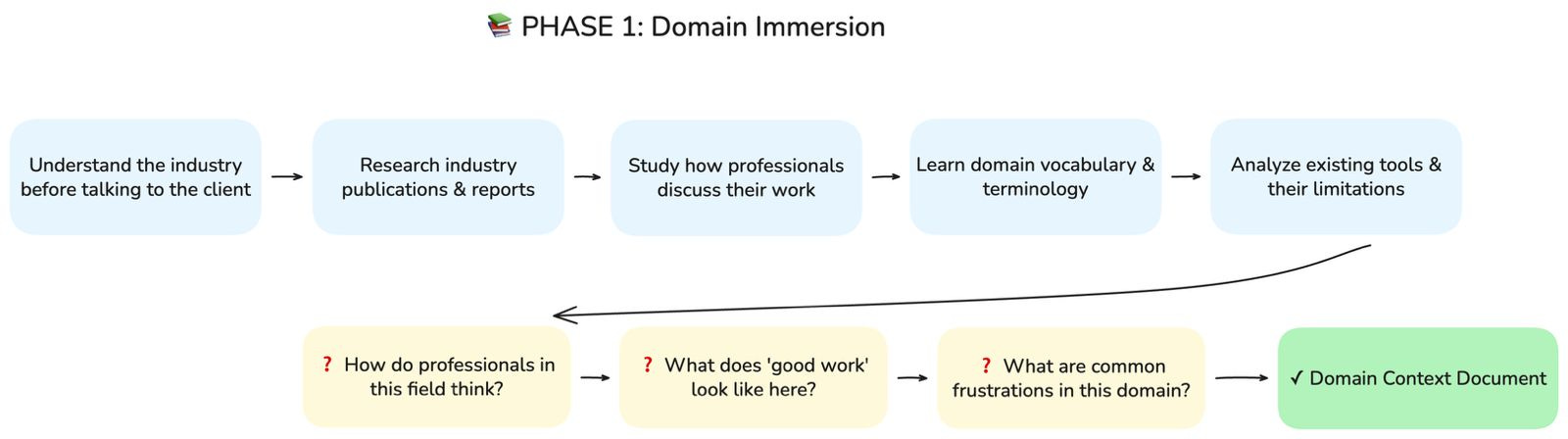

Phase 1: Domain Immersion

Before you speak to anyone at the client’s company, you need to understand the world they operate in. If you’re building a RAG system for a legal tech company, you don’t start by asking what documents they want to ingest, you start by understanding how lawyers actually think and work.

This means research, and not the superficial kind.

You read about how contracts are structured and why. You learn what due diligence actually involves, what associates spend their first three years doing, what partners care about versus what junior lawyers care about. You learn the vocabulary, not because you need to impress anyone, but because you cannot ask good questions if you don’t understand the language your users speak.

I typically spend several days on this before any client interaction, reading industry publications, watching how professionals in that field discuss their work, understanding the tools they currently use and the complaints they have about those tools. When I finally sit down with the client, I want to be able to follow their explanations without asking them to define every third word.

Key questions to answer:

How do professionals in this field think?

What does “good work” look like in this domain?

What are the common frustrations and pain points?

Output: Domain Context Document, your foundational understanding of the industry before you touch anything client-specific.

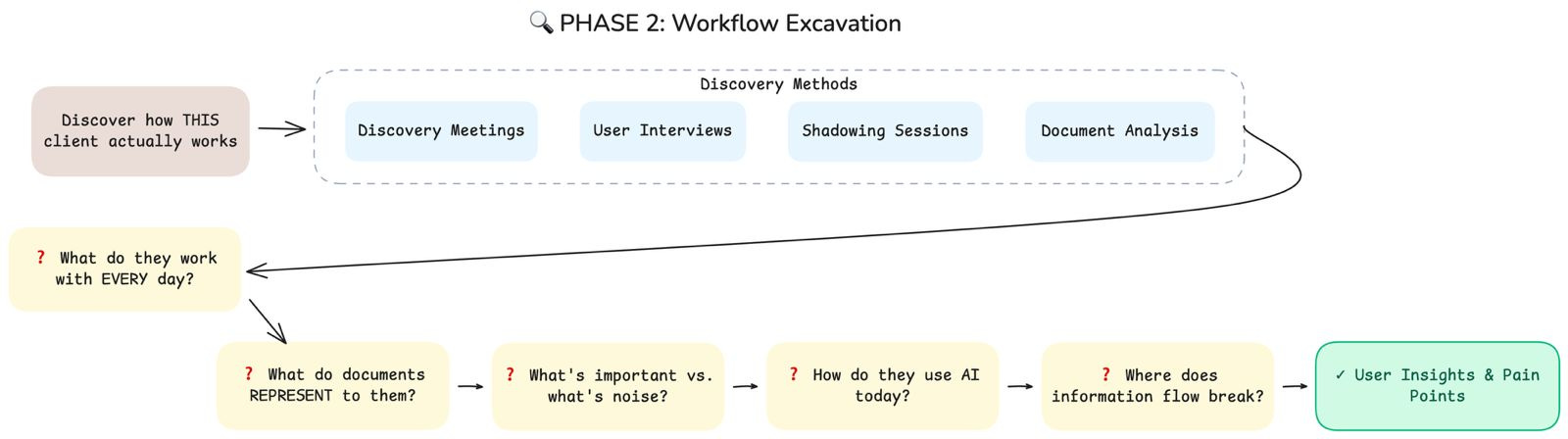

Phase 2: Workflow Excavation

Once you understand the domain, you need to understand this specific client’s reality. This is where discovery meetings, interviews, and shadowing come in.

The questions I ask in these sessions are not sophisticated.

They are, however, relentlessly practical.

I’m not trying to understand what people sometimes work with.

I’m not interested in theory or edge cases.

I want to understand the daily rhythm of their work.

What they touch every day.

What consumes their attention.

What quietly drains their time.

When someone works with contracts, for example, I dig into specifics:

Which types of contracts take up most of their time?

Which sections they always read carefully.

Which sections they instinctively skim.

What they’re actively looking for when they open a document.

What makes them hesitate. What makes them nervous.

That’s where the real signal is.

I pay particular attention not just to what documents contain, but to what they represent to the people using them.

A contract isn’t just a collection of clauses.

It’s a risk assessment.

A record of past negotiations.

A living relationship with a counterparty.

Understanding what a document means to its user tells you far more about how to model your data than any structural analysis ever will.

I also ask about their current relationship with AI and other tools.

Are they already using ChatGPT on the side, copying and pasting documents into it despite security policies?

Do they trust AI-generated summaries, or do they always verify everything manually? Have they been burned by automation before?

These questions reveal expectations and resistance that will shape adoption far more than your retrieval accuracy ever will.

Key questions to answer:

What do they work with every single day?

What do documents represent to them, beyond their content?

What is important versus what is noise?

How do they use AI today, if at all?

Where does information flow break down?

Output: User Insights & Pain Points, a clear picture of how this specific organization actually works.

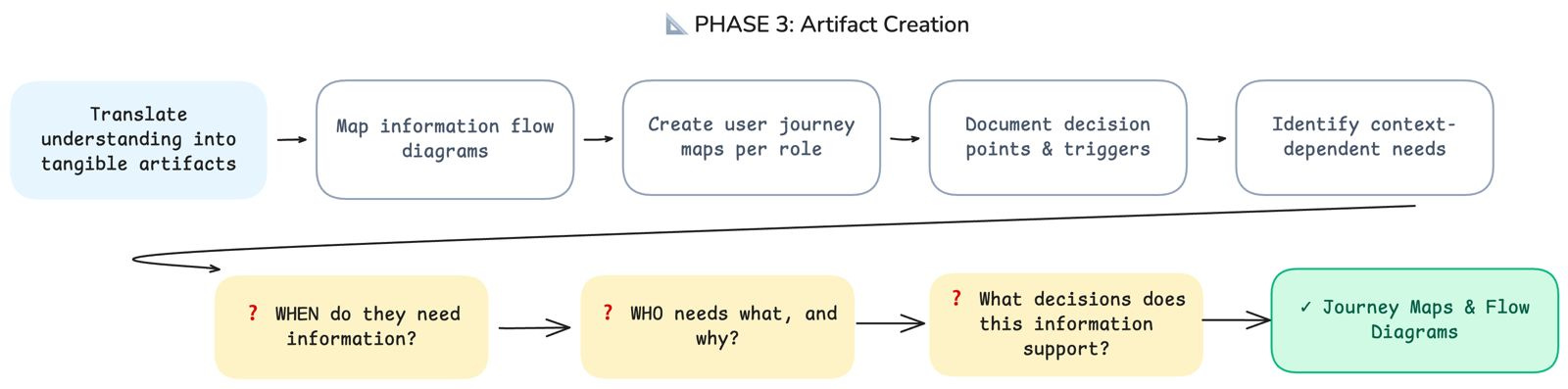

Phase 3: Artifact Creation

As I conduct interviews and shadow users, I translate what I learn into two primary artifacts:

Diagrams that map the information flow through their processes

User journey maps that capture how different roles interact with documents and systems at different moments.

These artifacts serve two purposes.

First, they force me to structure my understanding, the act of drawing a diagram reveals gaps in my knowledge and assumptions I hadn’t noticed I was making.

Second, they become communication tools that I can share back with the client to verify my understanding.

The journey maps are particularly important because they highlight the when of information needs, not just the what. A lawyer searching for a precedent clause at the start of a negotiation has very different needs than the same lawyer reviewing that clause during final contract review. Same document, same user, completely different context, and therefore completely different retrieval requirements.

Key questions to answer:

When do they need information, and in what context?

Who needs what, and why?

What decisions does this information support?

Output: Journey Maps & Flow Diagrams, visual representations of how information moves through the organization and how different roles interact with it.

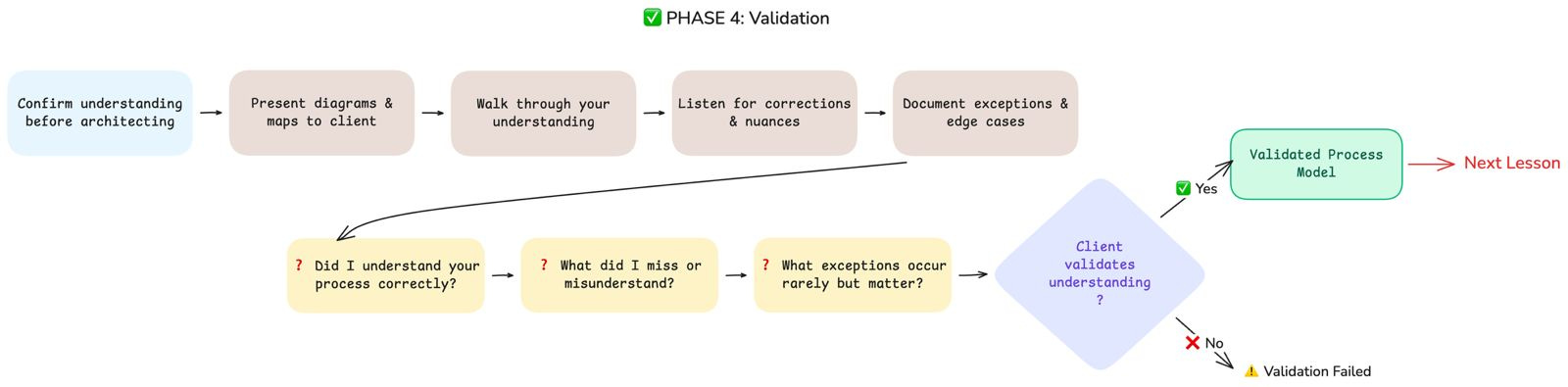

Phase 4: Validation

The final phase is the one most teams skip, and it’s the one that separates successful projects from expensive failures.

Before I design any architecture or write any code, I present my understanding back to the client and ask them to validate it.

I walk them through my diagrams and journey maps. I explain what I believe their process looks like, where I think the pain points are, what I think they’re trying to achieve when they search for information. And then I shut up and listen.

This is the moment when you discover everything you got wrong. The client will correct your assumptions, add nuances you missed, point out exceptions that occur rarely but matter enormously. They will tell you about the political dynamics that influence who uses what tools, the historical reasons why certain processes exist, the previous failed attempts at automation that have made certain teams skeptical.

Key questions to answer:

Did I understand your process correctly?

What did I miss or misunderstand?

What exceptions occur rarely but matter enormously?

Output: Validated Process Model, a client-approved understanding of their reality that you can now translate into technical decisions.

Critical rule: I don’t move to architecture until the client confirms that my understanding of their process is accurate.

Not approximately accurate, actually accurate. Because every error in your understanding at this stage becomes an architectural decision that doesn’t quite fit, a retrieval result that’s technically relevant but practically useless, a system that works in demos but fails in daily use.

If validation fails, and sometimes it does, you go back to Phase 2 with new focus areas and iterate until you get it right

From Process to Data Model

Once you have a validated understanding of the business process, something remarkable happens: your technical decisions start making themselves.

Everything you excavated directly shapes how you’ll model your data:

Chunking strategy becomes obvious when you understand how users consume information. If lawyers need clause context, you chunk at clause boundaries, not arbitrary token limits. If sales reps scan for specific terms, your chunks preserve those terms as coherent units.

Metadata schema emerges from how users filter and navigate. Different departments viewing the same documents? Your metadata supports that segmentation. Temporal context matters? That’s a first-class field, not an afterthought.

Retrieval approach follows from query patterns. Exhaustive results for due diligence means optimizing for recall. Quick answers during a live meeting means precision and speed.

User segmentation flows directly from your journey maps. Different roles get different retrieval configurations, not as a nice-to-have, but as core architecture.

This is why the Process Archaeologist framework exists. Not because business understanding is pleasant, but because it makes every technical decision coherent instead of arbitrary.

What’s next

This article covered the foundation: understanding why you’re building and who you’re building for.

In the next article, we go technical.

We’ll dive into data modeling for a RAG which really works, how to translate your validated process understanding into concrete decisions about document structure, chunking strategies, metadata schemas, and retrieval configurations.

I’ll walk through real examples, show you the tradeoffs, and share an open-source repository with production-ready patterns you can adapt for your own projects.

Because once you know why you’re building something, you need to figure out what to feed it.

Absolutely phenominal breakdown of enterprise AI implementaion. The Process Archaeologist framework resonates so much with my own experience. I've seen so many RAG projects fail because teams jumped straight into vector databases and embedding models without understanding the actual human workflow. The chrome extension example is spot-on — one size definetly does not fit all in enterprise contexts, even within the same company.

The Process Archaeologist framework is brilliant.

Too many teams skip straight to architecture without understanding the actual workflow they're supporting.

'Leave your technical ego at home' — this should be tattooed on every engineer's forehead.

The gap between 'technically elegant' and 'actually useful' is where most enterprise AI projects die.