Data Modeling for RAG That Works

Business understanding → Data modeling — Part 2/6 of RAG That Works

Before building any AI solution, take one minute to ask yourself: what is the underlying human process?

And if i made you curious let me also ask you some questions.

How many times did you feel that your technical decisions are not good?

How many times did you feel the impostor syndrome, because that you are not sure about your decisions?

We’re living in an era where everything moves at lightning speed. Everything must be done yesterday. We’ve stopped focusing on process, on understanding things in depth. We ship fast, we iterate fast, we burn out fast.

I’ve been there. Many times.

And I think this is part of my mission now: to tell you that it’s okay not to be up to date with every new framework and model release. It’s okay to feel the impostor syndrome. What’s not okay is letting that pressure push you into building things you don’t understand or because of hype.

This series is about slowing down just enough to build something that actually works.

PS: AI is not everything. We still bring our own brain, personality, and identity, and that remains irreplaceable.

In Part 1, I asked you to leave your technical ego at home. Now let’s see what happens when you actually do that.

Last time, we talked about the Process Archaeologist framework, understanding the human process before building any AI solution. Today, we translate that understanding into something concrete: the data model.

Let’s do an exercise. I’m going to show you a real system I built for manufacturing service manuals, 500+ page PDFs filled with torque specifications, hydraulic diagrams, fault codes, and maintenance procedures.

The kind of documents where getting the wrong answer could cost someone a finger. (joke).

But yes, complicated documents, with a lot of diagrams, tables, images and multiple links between pages.

The data model I’ll show you didn’t come from a whiteboard session about “best practices.” It came from watching technicians flip through manuals, curse at tables that span three pages, and squint at diagrams while grease dripped from their hands.

Let’s think & create.

The Domain: Manufacturing Service Manuals

Before I show you any code, let me describe what we’re dealing with.

A service manual for industrial telehandlers (think massive forklifts) contains:

Specifications tables: Torque values, fluid capacities, pressure ratings, often specific to model variants (642, 943, 1055, 1255)

Procedural instructions: Step-by-step maintenance and repair procedures

Diagrams and figures: Exploded parts views, hydraulic schematics, wiring diagrams

Fault codes: Diagnostic tables with SPN/FMI codes and descriptions

Safety warnings: CAUTION and WARNING blocks that must not be missed

Here’s what makes this domain particularly challenging:

Content spans pages: A torque specification table might start on page 35 and continue through page 37

Figures reference text, text references figures: “Tighten bolt to 85 Nm (see Figure 3-2)”

Model-specific variations: The same procedure differs between the 642 and 1255 models

Tables are dense with critical data: Miss one value, and you’ve overtorqued a hydraulic fitting

Traditional RAG approaches, chunk by 512 tokens, embed, retrieve, would destroy this content. A chunk boundary could land in the middle of a torque table. A figure reference would point to nothing. Model-specific instructions would get mixed together.

The data model has to understand this domain.

What You’ll Learn in This Article

By the end of Part 2, you’ll understand:

Why pages (not token chunks) are the right retrieval unit for technical documents

How a three-page sliding window preserves cross-page context without processing entire documents at once

A complete table extraction pipeline: structure preservation → metadata extraction → semantic flattening

How to construct embedding text that captures domain-specific relationships

Multi-vector indexing strategies for hybrid retrieval

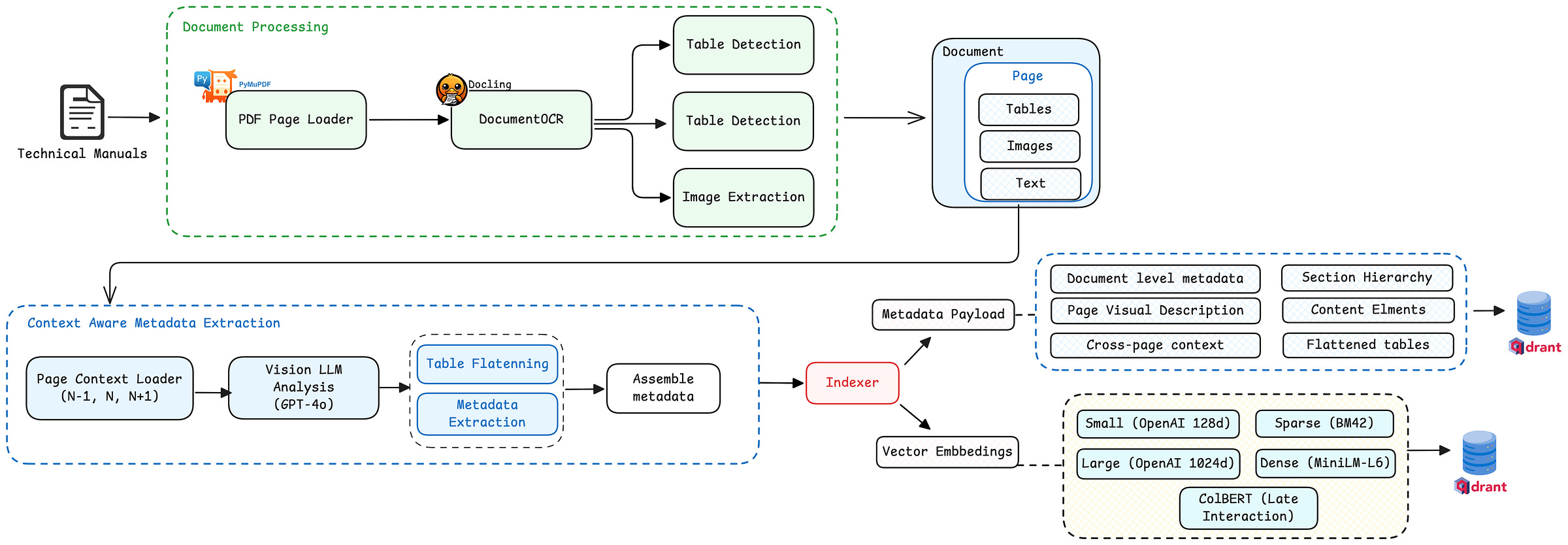

Here’s the system architecture we’ll build:

Let’s unpack each decision.

Decision 1: The Unit of Retrieval

The first architectural decision: what is your retrieval unit?

Most RAG tutorials say “chunk your documents into ~500 token pieces.” This advice works fine for blog posts and documentation. It fails catastrophically for technical manuals.

Here’s why I chose full pages as my retrieval unit:

Traditional RAG:

PDF → Split by tokens → Embed chunks → Retrieve fragments

Manufacturing RAG:

PDF Page → Extract structure → Tables + Figures + Text → Unified page metadata → Embed

Rationale:

Visual coherence: A page is how technicians actually consume information. They see the whole page, not a text fragment.

Structural integrity: Tables stay intact. Figure references stay near their figures.

Multimodal grounding: I can store the page image alongside extracted content, enabling visual verification.

The extraction pipeline processes each page independently, producing this folder structure:

scratch/service_manual_long/

├── page_36/

│ ├── page_36_full.png # Full page scan

│ ├── metadata_page_36.json # Basic extraction info

│ ├── context_metadata_page_36.json # Rich semantic metadata

│ ├── tables/

│ │ ├── table-36-1.html # Structured table

│ │ └── table-36-1.png # Table image

│ ├── images/

│ │ ├── image-36-1.png # Extracted figure

│ │ └── image-36-2.png

│ └── text/

│ └── page_36_text.txt # OCR text content

Each page becomes a self-contained unit with all its modalities preserved.

Decision 2: The Three-Page Context Window

Here’s where domain understanding pays off.

When a technician opens a service manual to page 36, they don’t see page 36 in isolation. They’ve been reading from page 34. They’ll continue to page 37. Context flows across page boundaries.

A torque specification table that starts on page 35 doesn’t suddenly become irrelevant when you turn to page 36, it’s still the same table, still the same procedure.

This insight led to my most important data modeling decision: extract metadata using a three-page sliding window.

When processing page N, the system simultaneously analyzes:

Page N-1 (previous page)

Page N (current page)

Page N+1 (next page)

Here’s the actual extraction function signature:

def extract_metadata_from_page(

litellm_client: LitellmClient,

image_path_n: str, # Current page image

image_path_n_1: str, # Previous page image

image_path_n_plus_1: str, # Next page image

metadata_page_n_1_path: str, # Previous page metadata

metadata_page_n_path: str, # Current page metadata

metadata_page_n_plus_1_path: str, # Next page metadata

page_n_1_text_path: str, # Previous page OCR text

page_n_text_path: str, # Current page OCR text

page_n_plus_1_text_path: str, # Next page OCR text

) -> str:

The LLM receives:

Three page images — visual context

Three OCR text files — textual context

Three metadata files — structural context (what tables/figures exist on each page)

This enables the model to understand:

“This table is a continuation from page 35”

“This procedure continues onto page 37”

“Figure 35-4 on the previous page is related to this text block”

The Cross-Page Context Schema

The extracted metadata includes explicit cross-page relationships:

{

"content_elements": [

{

"type": "table",

"element_id": "table-560-1",

"title": "Electrical System Fault Codes",

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": true,

"continues_on_next_page": true,

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["table-559-1"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["table-561-1"]

}

}

]

}

The magic here is that we are using the knowledge we learnt from the discovery meeting and model the data for the client needs.

The LLM explicitly determines whether content spans pages by comparing what it sees across the three-page window.

The Prompt That Drives It (full version on Github)

The extraction prompt explicitly instructs the model to handle cross-page relationships:

You will receive three consecutive PDF pages:

Previous page (N-1)

Current page (N) (Your primary focus)

Next page (N+1)

Use these to:

- Detect if any content on page N is continued from N-1

or continues onto N+1.

- Extract key entities, warnings, context, or model mentions

that may not be confined to a single page.

- Provide summaries for text blocks and relate them to

tables and figures accurately.

And the schema enforces it:

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": "<true|false>",

"continues_on_next_page": "<true|false>",

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["<element IDs from N-1>"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["<element IDs from N+1>"]

}

Why does this matter?

When a user asks “What are the fault codes for the Diesel Exhaust Fluid Dosing Unit?”, the retrieval system doesn’t just return page 560. It knows that page 560’s table continues from 559 and onto 561. The answer generation can pull context from the entire spanning structure.

Why Pages Can Be Independent Units (Even for Multi-Page Tables)

Here’s a question I get asked: “If a table spans 10 pages, don’t you lose coherence by treating each page separately?”

The answer is no, and the three-page window is why.

Consider a specification table that spans pages 24 through 27 (like our fluid capacities table). Each page gets processed with its neighbors:

Page 24: sees [23, 24, 25] → knows it starts a new table, continues to 25

Page 25: sees [24, 25, 26] → knows it continues from 24, continues to 26

Page 26: sees [25, 26, 27] → knows it continues from 25, continues to 27

Page 27: sees [26, 27, 28] → knows it continues from 26, table ends here

This creates a chain of overlapping context. Every page knows:

What came before it (from N-1)

What comes after it (from N+1)

That it’s part of a larger structure

The metadata captures this explicitly:

// Page 25's metadata

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": true,

"continues_on_next_page": true,

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["table-24-1"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["table-26-1"]

}

// Page 26's metadata

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": true,

"continues_on_next_page": true,

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["table-25-1"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["table-27-1"]

}

At retrieval time, when page 25 is relevant, we can follow the chain: 25 → 24, 25 → 26 → 27.

The table is reconstructable even though each page was processed independently.

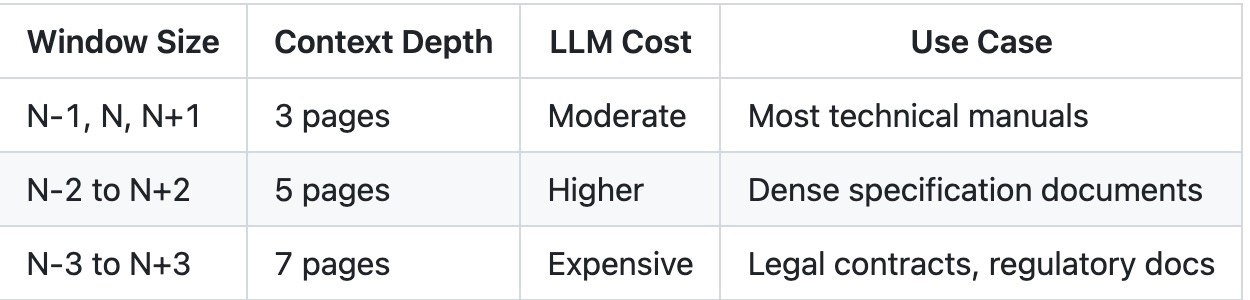

Extending to N-2, N-1, N, N+1, N+2

The same principle scales. For very complex documents — where context dependencies span further — you can extend the window:

Page N sees: [N-2, N-1, N, N+1, N+2]

This gives each page awareness of content two pages away in either direction. The trade-offs:

For manufacturing service manuals, the 3-page window captures 95% of cross-page relationships.

The key insight: you don’t need to process a 10-page table as a single unit. The sliding window progression means each page carries enough context to reconstruct the whole.

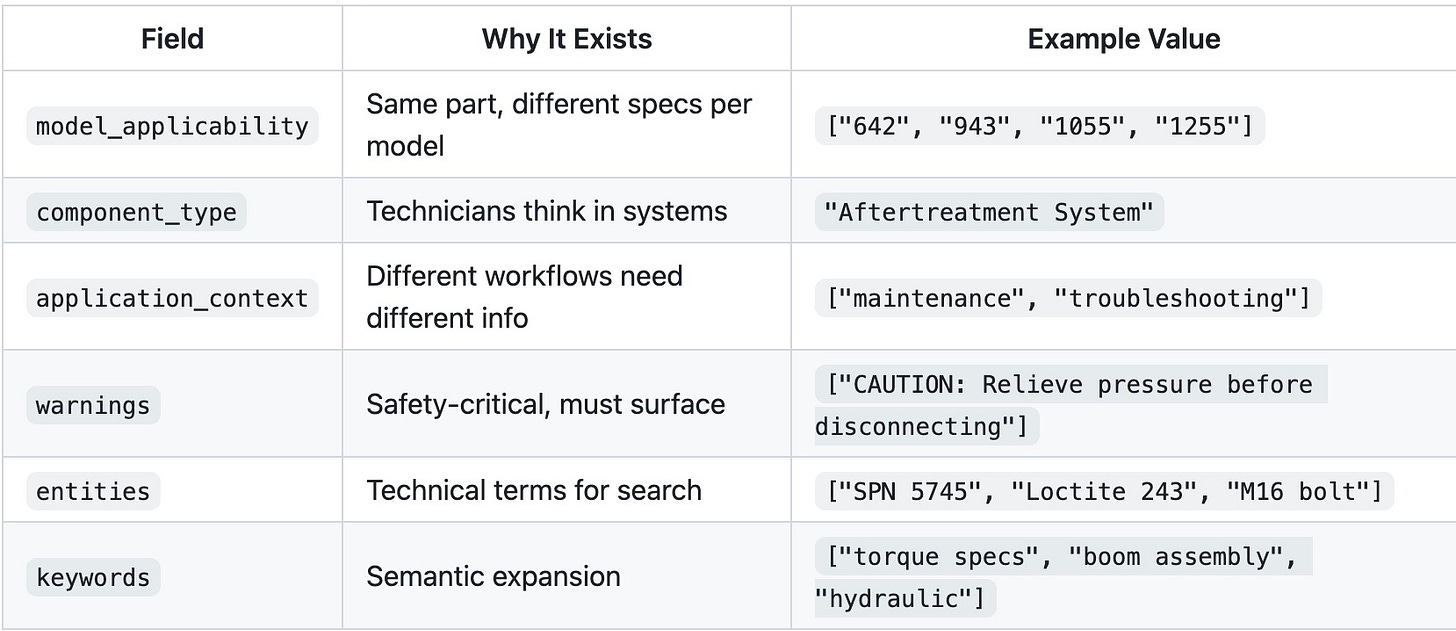

Decision 3: Domain-Specific Metadata Fields

Generic metadata (title, date, author) tells you nothing useful for retrieval in specialized domains.

The metadata schema I designed came directly from understanding how technicians think about their work:

Here’s a real metadata entry from page 36:

{

"document_metadata": {

"document_title": "General Information and Specifications",

"document_id": "31211033",

"document_type": "Service Manual",

"models_covered": ["642", "742", "943", "1043", "1055", "1255"]

},

"page_number": "36",

"page_visual_description": "The page primarily features a large diagrammatic

illustration of a vehicle, with callouts and symbols indicating specific

parts and maintenance points. The top includes a header with title

'General Information and Specifications' and subheading 'b. 1055, 1255'.

Symbols A and B denote different maintenance actions.",

"section": {

"section_number": "2.5.2",

"section_title": "250 Hour",

"subsection_number": "",

"subsection_title": ""

},

"content_elements": [

{

"type": "figure",

"element_id": "figure-36-1",

"title": "Vehicle Maintenance Points for Models 1055 and 1255",

"summary": "Illustration showing key maintenance points on the vehicle

for models 1055 and 1255, with callouts indicating lubrication

and inspection areas.",

"keywords": ["maintenance", "lubrication", "inspection", "1055", "1255"],

"entities": ["Model 1055", "Model 1255"],

"component_type": "Vehicle Maintenance",

"model_applicability": ["1055", "1255"],

"application_context": ["maintenance", "inspection"],

"within_page_relations": {

"related_figures": [],

"related_tables": [],

"related_text_blocks": []

},

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": true,

"continues_on_next_page": true,

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["figure-35-4"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["figure-37-1"]

}

}

]

}

Notice what’s captured:

Visual description — The LLM describes what’s actually on the page

Model applicability — This specific figure applies to 1055 and 1255 models only

Section context — It’s in the “250 Hour” maintenance schedule

Cross-page flow — This figure is part of a sequence spanning pages 35-37

Deep Dive: The Table Problem

Tables deserve their own section. In manufacturing documents, tables contain the most critical information, torque specs, fault codes, fluid capacities, part numbers, yet they’re the hardest content type for RAG systems to handle.

Let me walk you through exactly how we approached this.

Why Tables Break Traditional RAG

Consider this fluid capacities table from page 25 of our service manual. This is what technicians actually deal with, not a simple grid, but a hierarchical specification table with nested categories:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Hydraulic System │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ System Capacity │

│ ├── 642 │

│ │ ├── No Outriggers 40.2 gallons (152 liters) │

│ │ └── With Outriggers 41.7 gallons (158 liters) │

│ ├── 742 │

│ │ └── No Outriggers 40.2 gallons (152 liters) │

│ └── Reservoir Capacity 23.8 gallons (90 liters) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Axles │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Differential Housing Capacity │

│ ├── Front 7.6 quarts (7.2 liters) │

│ ├── Rear 7 quarts (6.6 liters) │

│ └── Friction Modifier Not to Exceed 12.2 oz (360 ml) │

│ (Must be premixed with axle fluid) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Now imagine chunking this by tokens. The disasters multiply:

Hierarchy destruction: “642” ends up separated from “No Outriggers”, which model does 40.2 gallons belong to?

Unit confusion: “7.6 quarts” in one chunk, “(7.2 liters)” in another

Conditional loss: “With Outriggers” separated from its value, now the capacity is ambiguous

Cross-model mixing: Values for 642 and 742 interleaved nonsensically

A technician searching “hydraulic fluid capacity for 642 with outriggers” would get garbage.

Stage 1: Structural Extraction with TableFormer

The first step is extracting tables with their structure intact. We use Docling with TableFormer in ACCURATE mode:

class DoclingOCRStrategy:

def __init__(self):

self.pipeline_options = PdfPipelineOptions()

self.pipeline_options.do_table_structure = True

self.pipeline_options.table_structure_options.do_cell_matching = True

self.pipeline_options.table_structure_options.mode = TableFormerMode.ACCURATE

This gives us:

Cell boundaries — Exact row/column positions

Header detection — Which rows are headers vs data

Merged cell handling — Common in spec tables

Every table gets saved in two formats:

page_560/

├── tables/

│ ├── table-560-1.html # Structured HTML

│ └── table-560-1.png # Visual snapshot

The HTML preserves the full structure:

<table>

<tbody>

<tr>

<th>SPN</th>

<th>FMI</th>

<th>Fault Code</th>

<th>SPN Description</th>

<th>Description</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>5745</td>

<td>3</td>

<td>4168</td>

<td>Aftertreatment 1 Diesel Exhaust Fluid Dosing Unit Heater</td>

<td>Voltage Above Normal, or Shorted to High</td>

</tr>

<!-- ... more rows ... -->

</tbody>

</table>

Stage 2: Table Metadata Extraction

Raw HTML isn’t enough. We need semantic understanding of what the table means.

For each table, we call a vision LLM with both the table image and its HTML:

def generate_table_metadata(

litellm_client: LitellmClient,

html_content: str,

pdf_page: str # Full page image for context

) -> dict:

resp = litellm_client.chat(

messages=[{

"role": "user",

"content": [

{"type": "text", "text": GENERATE_TABLE_METADATA_PROMPT},

{"type": "image_url", "image_url": {"url": page_image}},

{"type": "text", "text": f"<html>{html_content}</html>"},

],

}],

response_format=TableMetadataResponse,

)

The prompt emphasizes context awareness:

Tables in technical documents often depend heavily on their

surrounding context for interpretation. You must analyze nearby

text to accurately understand and summarize the table's purpose.

Critical context may include:

- Section headers, labels, or chapter titles

- Units of measurement and engineering specifications

- Footnotes or annotations

- Product models, standards, or part numbers

- Mentions of illustrations or figures (e.g., "see Fig. 3")

The output schema captures domain-specific metadata:

class TableMetadataResponse(BaseModel):

title: str # "Fault Codes for Aftertreatment Systems"

summary: str # What the table shows, in context

keywords: List[str] # ["fault codes", "DEF", "aftertreatment"]

entities: List[str] # ["SPN 5745", "Selective Catalytic Reduction"]

model_name: Optional[str] # Which machine model

component_type: Optional[str] # "Aftertreatment System"

application_context: List[str] # ["troubleshooting", "diagnostics"]

related_figures: List[RelatedFigure] # Figures that explain this table

Here’s actual metadata extracted from the fault codes table:

{

"title": "Fault Codes for Aftertreatment Systems",

"summary": "Lists fault codes related to various aftertreatment components,

including sensors and heaters, indicating issues such as voltage

abnormalities and data validity problems. Crucial for diagnosing

and troubleshooting diesel exhaust systems.",

"keywords": [

"fault codes", "aftertreatment", "diesel exhaust",

"sensors", "heaters", "voltage issues", "diagnostics"

],

"entities": [

"Selective Catalytic Reduction",

"Diesel Exhaust Fluid Dosing Unit",

"Outlet Soot Sensor"

],

"component_type": "Aftertreatment System",

"application_context": ["diesel engines", "emission control", "vehicle diagnostics"]

}

Now we know what this table is about, not just what it contains.

Stage 3: Table Flattening for Semantic Search

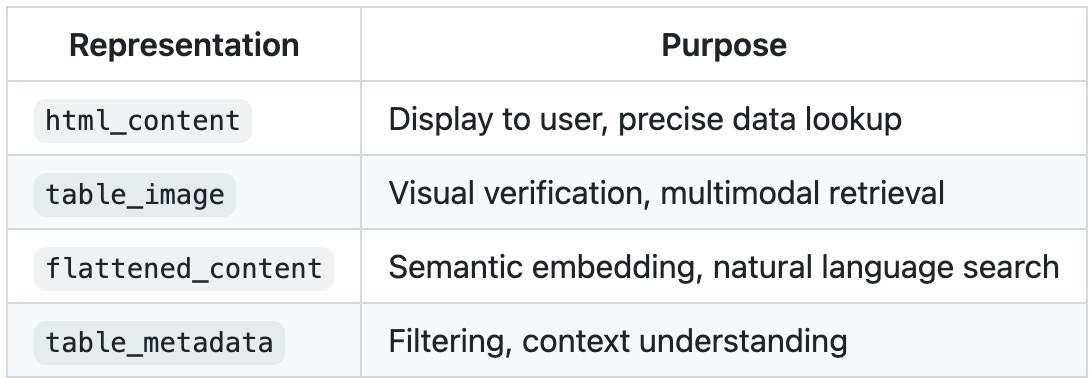

Here’s the key insight: tables need to exist in two forms.

Structured — For display and precise lookup

Flattened — For semantic embedding and search

The flattening prompt is deliberately verbose:

FLATTEN_TABLE_PROMPT = """

You are given a table in HTML format.

Your task:

- Flatten this table into a clear, human-readable paragraph.

- Include *every significant piece of data* from the table: titles,

component names, values, units, material names, codes, and properties.

- Preserve structure and associations, e.g. which value corresponds

to which component.

- Do not omit or generalize any rows or key values.

- Ensure no technical information from the table is lost.

Your outputs will be embedded into a vector index for retrieval.

"""

The result transforms hierarchical structure into searchable prose that preserves all relationships:

"The table describes various fluid capacities for different vehicle systems.

The hydraulic system capacities vary: for the 642 model with no outriggers,

it is 40.2 gallons (152 liters), and with outriggers, it is 41.7 gallons

(158 liters). For the 742 model with no outriggers, it remains 40.2 gallons

(152 liters), and the reservoir capacity to the full mark is 23.8 gallons

(90 liters).

The axles' differential housing capacity is 7.6 quarts (7.2 liters) for the

front and 7 quarts (6.6 liters) for the rear, with a friction modifier limit

of 12.2 ounces (360 milliliters) to be premixed with axle fluid. The wheel

end capacity is 1.2 quarts (1.1 liters) for the front and 1.4 quarts

(1.3 liters) for the rear..."

Notice what the flattening accomplished:

Model association preserved: “for the 642 model with no outriggers, it is 40.2 gallons”

Conditional context retained: “with outriggers, it is 41.7 gallons”

Units kept together: “7.6 quarts (7.2 liters)”

Nested relationships explicit: “friction modifier... to be premixed with axle fluid”

Now when someone searches “hydraulic capacity 642 with outriggers”, the embedding model matches semantically and precisely.

Stage 4: The Complete Table Record

In the final metadata, each table exists as a complete record with all representations:

{

"flattened_tables": [

{

"table_id": "table-25-1",

"html_file": "table-25-1.html",

"html_content": "<table><tbody>...</tbody></table>",

"flattened_content": "The table describes various fluid capacities..."

}

],

"table_metadata": [

{

"table_id": "table-25-1",

"title": "Fluid and System Capacities for Vehicle Components",

"summary": "Provides detailed fluid capacities for various vehicle systems,

including fuel, cooling, hydraulic, and transmission. Also covers

differential housing and wheel end capacities with model-specific values.",

"keywords": [

"fluid capacities", "hydraulic system", "differential housing",

"wheel end capacity", "transmission system", "cooling system"

],

"entities": ["642", "742", "ULS 110 HP", "130 HP"],

"component_type": "Vehicle Systems",

"application_context": ["vehicle maintenance", "fluid management"],

"table_file": "table-25-1.html",

"table_image": "table-25-1.png"

}

],

"cross_page_context": {

"continued_from_previous_page": true,

"continues_on_next_page": true,

"related_content_from_previous_page": ["table-24-1"],

"related_content_from_next_page": ["table-26-1"]

}

}

Notice the cross_page_context, this capacities table actually spans pages 24-27, with different models on each page (642/742 on pages 24-25, 943/1043 on page 26, 1055/1255 on page 27).

This gives us:

Why This Matters

A technician types: “What’s the hydraulic fluid capacity for a 642 with outriggers?”

With traditional chunking: Garbage. The table is fragmented. “642” is in one chunk, “With Outriggers” in another, “41.7 gallons” somewhere else. The model hallucinates a number or says “I don’t know.”

With our approach:

Flattened content matches “hydraulic capacity 642 outriggers” semantically

Table metadata confirms this is about “Vehicle Systems” and “fluid management”

Model applicability filters to 642-relevant pages

HTML structure lets us display the exact row with both gallons and liters

Cross-page context tells us pages 26-27 have values for other models (943, 1043, 1055, 1255)

The answer: “The hydraulic system capacity for the 642 with outriggers is 41.7 gallons (158 liters). Without outriggers, it’s 40.2 gallons (152 liters). The reservoir capacity to full mark is 23.8 gallons (90 liters).”

And if the technician follows up with “What about the 1055?” — we know exactly where to look: page 27, table-27-1, because the cross-page context mapped the entire capacities section.

That’s what good data modeling enables.

Decision 5: The Embedding Text Construction

Why Raw Text Fails

You might think: “Just embed the OCR text from each page.” Here’s what that looks like for page 36:

That’s it. That’s what the OCR extracted. No context about what “A” and “B” mean. No indication this is a maintenance schedule. No connection to the models it applies to.

A search for “250 hour maintenance 1055” might not even match this page — the semantic signal is too weak.

The metadata we extracted in previous steps contains rich semantic information. The question is: how do we get that into the embedding?

What actually gets embedded? Not the raw page text. Not the raw metadata JSON.

I construct a purpose-built embedding text that combines structured metadata with content:

def build_embedding_text_from_page_metadata(metadata: dict) -> str:

"""Extract structured text from page metadata for embedding generation."""

doc = metadata.get("document_metadata", {})

section = metadata.get("section", {})

page_number = metadata.get("page_number", "")

content_elements = metadata.get("content_elements", [])

# Header

header = [

f"Document: {doc.get('document_title', '')} "

f"({doc.get('manufacturer', '')}, Revision {doc.get('document_revision', '')})",

f"Section: {section.get('section_number', '')} {section.get('section_title', '')}",

f"Subsection: {section.get('subsection_number', '')} {section.get('subsection_title', '')}",

f"Page: {page_number}",

]

# Content summaries

body = []

for el in content_elements:

el_type = el.get("type", "")

title = el.get("title", "")

summary = el.get("summary", "")

if el_type == "text_block":

body.append(f"Text Block: {title}\nSummary: {summary}")

elif el_type == "figure":

body.append(f"Figure: {title} – {summary}")

elif el_type == "table":

body.append(f"Table: {title} – {summary}")

# Aggregated metadata for semantic matching

all_entities = set()

all_keywords = set()

all_warnings = set()

all_models = set()

for el in content_elements:

all_entities.update(el.get("entities", []))

all_keywords.update(el.get("keywords", []))

all_warnings.update(el.get("warnings", []))

all_models.update(el.get("model_applicability", []))

tail = [

f"Entities: {', '.join(sorted(all_entities))}" if all_entities else "",

f"Warnings: {', '.join(sorted(all_warnings))}" if all_warnings else "",

f"Keywords: {', '.join(sorted(all_keywords))}" if all_keywords else "",

f"Model Applicability: {', '.join(sorted(all_models))}" if all_models else "",

]

return "\n\n".join(part for part in (header + body + tail) if part)

This produces embedding text like:

Document: General Information and Specifications (Revision )

Section: 2.5.2 250 Hour

Page: 36

Figure: Vehicle Maintenance Points for Models 1055 and 1255 –

Illustration showing key maintenance points on the vehicle for

models 1055 and 1255, with callouts indicating lubrication and

inspection areas.

Entities: Model 1055, Model 1255

Keywords: inspection, lubrication, maintenance, 1055, 1255

Model Applicability: 1055, 1255

The embedding captures:

What the page contains (figures, tables, text)

Where it sits in the document structure (section 2.5.2)

Which models it applies to (1055, 1255)

What concepts it covers (lubrication, inspection, maintenance)

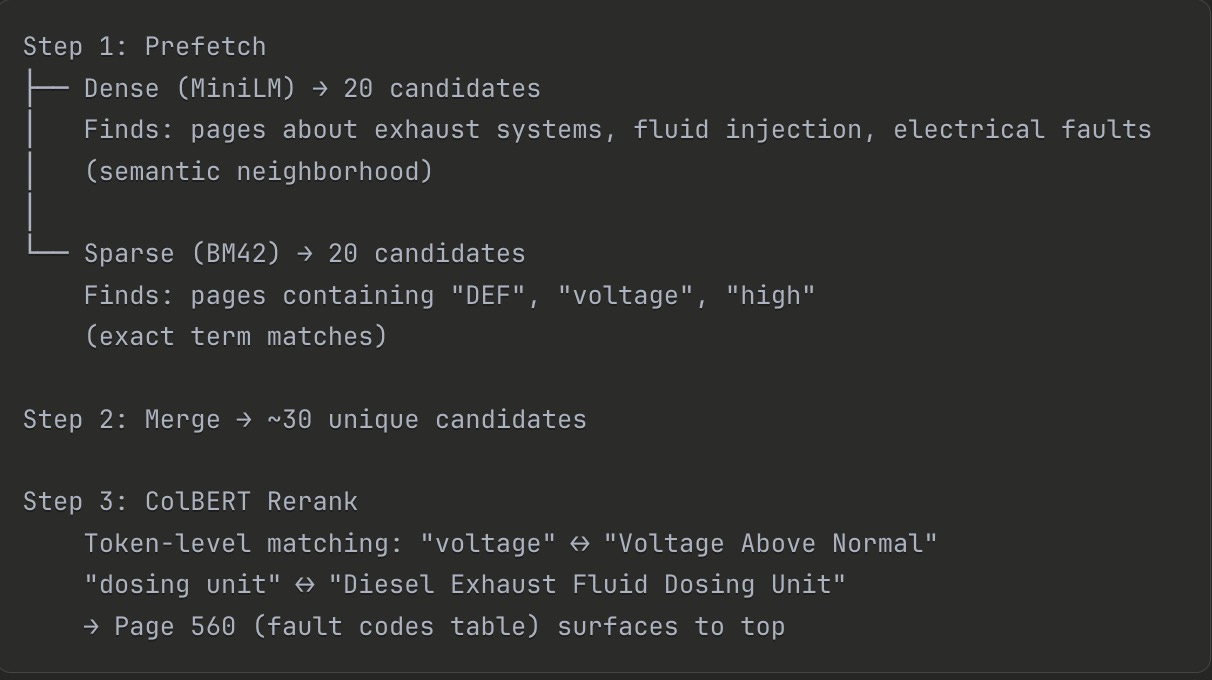

Decision 6: Multi-Vector Indexing

The Query Spectrum Problem

Watch these three real queries hit the same system:

“hydraulic system problems” — Semantic. The user wants conceptually related content.

“SPN 5745” — Exact match. This is a specific fault code. Close isn’t good enough.

“DEF dosing unit voltage high” — Hybrid. Some terms are exact (”DEF”, “voltage”), some are semantic (”dosing unit” ≈ “injection system”).

A single embedding strategy forces a tradeoff:

Dense embeddings excel at query 1, fail at query 2 (SPN 5745 embeds similarly to SPN 5746)

Sparse/keyword matching nails query 2, misses query 1 (no exact word overlap)

Neither handles query 3 well alone

You need all three — and a way to combine them.

A single embedding strategy isn’t enough for technical content. Different query types need different matching approaches.

I index each page with five vector types:

vectors_config={

# Dense semantic matching

"dense": models.VectorParams(

size=384, # MiniLM-L6

distance=models.Distance.COSINE,

),

# Late interaction for precise matching

"colbert": models.VectorParams(

size=128, # ColBERTv2

distance=models.Distance.COSINE,

multivector_config=models.MultiVectorConfig(

comparator=models.MultiVectorComparator.MAX_SIM

),

),

# OpenAI embeddings at different granularities

"small-embedding": models.VectorParams(size=128, ...),

"large-embedding": models.VectorParams(size=1024, ...),

},

# Keyword matching

sparse_vectors_config={

"sparse": models.SparseVectorParams(...) # BM42

}

The retrieval pipeline uses hybrid search:

def retrieve(self, query: str, limit: int = 5) -> List[Dict]:

# Generate all query embeddings

dense_vector = next(self.dense_model.embed(query)).tolist()

sparse_vector = next(self.sparse_model.embed(query))

colbert_vector = next(self.colbert_model.embed(query)).tolist()

# Prefetch with dense and sparse

prefetch = [

models.Prefetch(query=dense_vector, using="dense", limit=20),

models.Prefetch(query=sparse_vector, using="sparse", limit=20),

]

# Rerank with ColBERT

results = self.client.query_points(

collection_name=collection_name,

prefetch=prefetch,

query=colbert_vector,

using="colbert",

limit=limit,

)

return self._format_results(results)

How They Work Together

Here’s query 3 (”DEF dosing unit voltage high”) flowing through the pipeline:

Dense found the right neighborhood. Sparse ensured exact terms weren’t missed. ColBERT picked the winner by matching at token granularity.

No single vector type could do this alone.

Decision 7: Query Decomposition

Complex questions need decomposition before retrieval.

When a technician asks: “What’s the difference in axle fluid capacity between models 943 and 1255?”

This isn’t one retrieval query. It’s multiple:

USER_QUESTION_DECOMPOSITION_PROMPT = """

You are an expert assistant that breaks down complex technical questions.

Decompose the question into reasoning-enhancing sub-questions:

- Fact-finding sub-questions (specifications, values)

- Comparative sub-questions (model differences)

- Contextual sub-questions (maintenance implications)

Each sub-question must be mapped to the correct section of the manual.

"""

The decomposition output:

[

{

"sub_question": "What are the front axle differential housing capacities for models 943 and 1255?",

"section_number": 2,

"section_title": "General Information and Specifications",

"matched_chapters": ["Fluid and Lubricant Capacities"]

},

{

"sub_question": "What are the rear axle differential housing capacities for models 943 and 1255?",

"section_number": 2,

"matched_chapters": ["Fluid and Lubricant Capacities"]

},

{

"sub_question": "How does the difference in axle fluid capacity affect lubrication frequency?",

"section_number": 2,

"matched_chapters": ["Lubrication Schedule", "Service and Maintenance Schedules"]

}

]

Each sub-question gets retrieved independently, and the results are combined for answer generation.

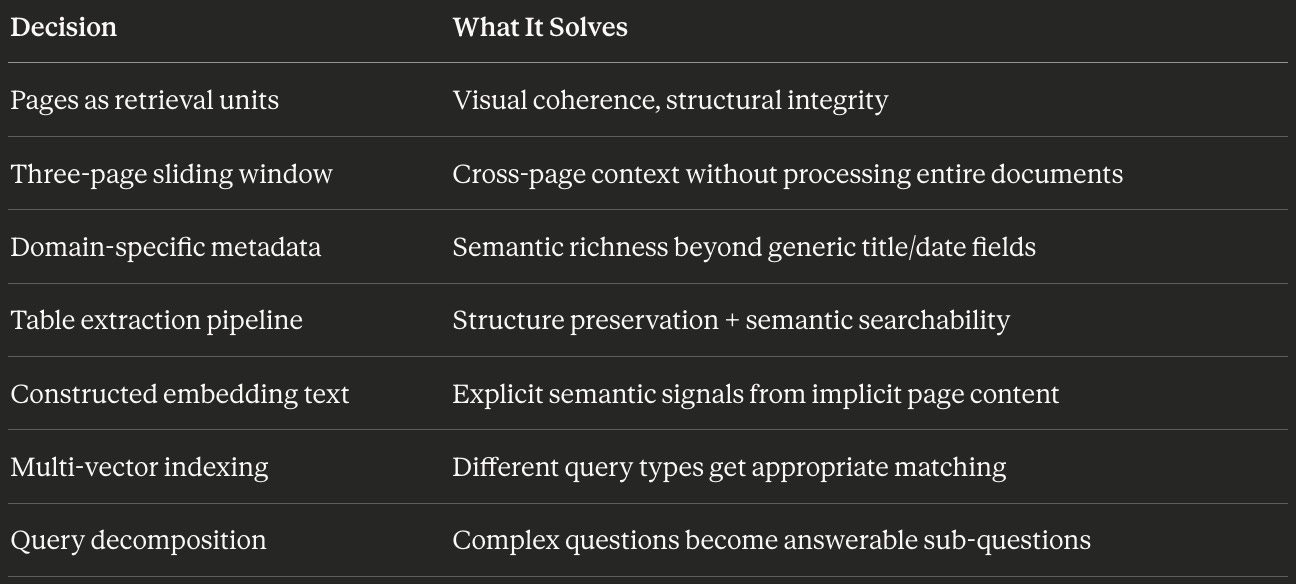

What We Built

Let’s step back and see what we’ve created.

We started with a problem: 500+ -page service manuals filled with spanning tables, cross-referenced figures, and model-specific specifications. Traditional RAG would have shredded this content into meaningless fragments.

Instead, we built a data model that respects the domain:

None of these decisions came from a “RAG best practices” blog post. They came from understanding how technicians actually use service manuals, flipping between pages, tracing figure references, comparing specifications across models.

That’s the Process Archaeologist approach in practice. The human workflow shaped every technical choice.

The Indexing Reality Check

Here’s something I want you to sit with: we haven’t written a single retrieval query yet.

This entire article, all seven decisions, covers only the ingestion and indexing pipeline. We’ve taken raw PDFs and transformed them into a richly structured, multi-vector indexed collection in Qdrant.

The retrieval and answer generation? That’s where this data model pays off. But it’s also where new challenges emerge:

How do you follow cross-page chains at query time?

When do you retrieve the table HTML vs. the flattened text?

How do you handle queries that span multiple document sections?

What does the actual retrieval → reranking → generation pipeline look like in code?

Coming in Part 3: The Table Deep Dive

The table extraction pipeline I showed you in Decision 4? That was the overview. In Part 3, we go deeper.

You’ll see:

The complete extraction code — from PDF page to structured HTML to flattened prose

Edge cases that break naive approaches — merged cells, nested headers, tables that span 10+ pages

The prompts that actually work — including the failures that taught me what to include

A working table extraction module you can adapt for your own domain

If this article helped you think differently about RAG data modeling, share it with someone building document AI systems. And if you want to discuss your own domain challenges, I'm always up for a conversation, sometimes the best insights come from seeing how these principles apply to problems I haven't encountered yet.